Grumman's Ascendancy

Of the several aircraft manufacturers struggling to survive in the dark economic days of the Great Depression, Grumman would set a standard of excellence that would be hard to match. How the company came to exist, and the story of its remarkable growth, resulted from the genius of three brilliant engineers and their tremendous drive to succeed.

In 1928, Grover Loening accepted an offer to sell the Loening Aircraft Engineering Company to a group of investment bankers. This would merge the assets of the Loening firm with that of the Keystone Aircraft Company. This would also entail moving the Loening operation to Keystone’s plant in Bristol, Pennsylvania.

With the move planned for late 1929, most of Loening’s employees were informed that their positions were secure if they elected to move with the company to Bristol. For many of Loening’s staff, such a move was not acceptable. Family ties, homes, and a genuine love for their communities were reasons enough not to uproot their lives and head off into the unknown. The three men responsible for actual running of Loening were less than enthused after a visit to the Keystone facility. Roy Grumman, Jack Swirbul and Bill Schwendler knew that there had to be a viable alternative. After discussions among themselves, and after obtaining the blessing and a bit of venture capital from Grover Loening, the three men set out to create their own aircraft manufacturing corporation.

To get any such venture underway, three things would be needed. Initial financing was to be supplied by the existing assets held by each man. This would be an “out of pocket” venture. Their second consideration had to be about acquiring a skilled work force. As 1929 wound down, the more skilled of Loening’s work force was approached about joining the new venture. Most of them signed on, preferring to take their chances with the new company rather than make the uncertain move to Keystone. Provided with a central core of skilled personnel, the chances of survival increased exponentially. Finally, a decision would have to be made as to which market would offer the best chance of success. Eventually, the determination was made to pursue the military market. Within weeks, this choice would be validated by the stock market crash, and the near collapse of the commercial aviation business within two years.

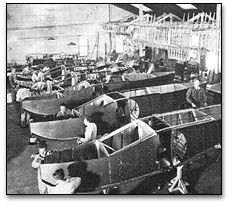

The Model A float was Grumman's first Navy contract. Here, the Grumman workforce assemble several floats inside the cramped Baldwin building. The cut-out for the retractable wheels are plainly visible near the center of each float. (Mfg. photo)

On December 5, 1929, the Grumman Aircraft Engineering Company became a reality, at least on paper. To become a functioning operation, a building was required. Jake Swirbul located and rented just such a building in the town of Baldwin, out on Long Island. Formerly the home of a small aircraft manufacturer, it had lately been used as an automobile dealership. The structure was in poor shape, with broken windows and junk strewn across the fl oor. Several fall seasons of dried leaves littered the factory's interior in heaps. It would require as enormous amount of time and elbow grease to get the facility ready, but the rent was cheap and at this point in the venture, that was paramount. Everyone would pitch in to get the new shop prepared. On January 2, 1930, the employees reported and Grumman Aircraft Engineering Corporation was open for business.

As the new company opened shop, the only work available was repairing Loening aircraft. However, it was readily apparent that there would not be enough repair work to keep the shop busy. A contract was negotiated with Motor Haulage Corporation for the manufacture of four aluminum truck bodies. The customer was so pleased with the quality of Grumman’s work that additional contracts were issued for many more truck and trailer bodies. Perhaps, some of the workforce tended to be a bit disillusioned at the lack of aviation work, but the truck body contracts provided income and security in the deepening national economic depression. Unlike many of their fellow Long Islanders, they at least, had a job.

Through his contacts in naval aviation, Roy Grumman learned that the Navy had become dissatisfied with the Vought designed amphibious floats fitted to their O2U-1 Scout planes. Bill Schwendler designed a new float equipped with retractable landing gear built in. After some considerable negotiations, the Navy accepted Grumman's proposal. Designated the Model A float, it was a better product than the competition offered and Grumman won contracts for the Model A and later, an improved float designated the Model B. During the discussions with the Navy over float procurement, Grumman was asked if a similar retractable landing gear could be retrofitted into their Boeing F4B-1 fighters. Roy Grumman was not especially interested in helping to improve the flying performance of their competitor’s aircraft. Instead, in March of 1930, a Grumman proposal was submitted for a new two-seat biplane fighter design with retractable landing gear. The proposal offered better performance than any fighter currently in U.S. Navy service. All that Grumman had to do now was wait.

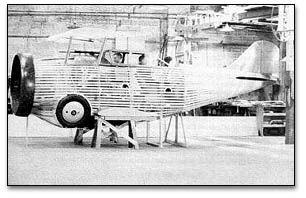

The manufacture of an aircraft is a complex undertaking, even back in 1931. To aid in the design, manufacture and fitting of the various components, a wood mockup was frequently constructed. This mockup of the XFF-1 sits in the Baldwin plant. Two Grumman employees have taken up the flight crew's positions. (Mfg. photo)

It would be a long wait. Finally, after 381 days, the navy responded with a contract for a single fighter, designated the XFF-1. A total of $46,875 was allocated for the new aircraft. To aid in the manufacturing process, a mockup was constructed of wood. Drawings were generated and the various components of the fighter were manufactured and assembly began. Gradually, the fighter began to take on the form of an airplane. With the fuselage completed, the wings were partially built up and installed. Not long after construction began on the XFF-1, a second prototype was ordered by the Navy. This was to be a Scout version of the plane, and was designated the XSF-1. It became immediately apparent that Grumman’s tiny shop in Baldwin was entirely too small to facilitate the building of a second aircraft. With another contract for floats expected, the space situation would be even more hopeless. It was time to find a new facility. A vacant Naval Reserve hanger was discovered adjacent to Curtiss Field out east in Valley Stream. Compared to the Baldwin shop, the hanger was quite satisfactory, and the rent was very reasonable. Alongside the hanger was a small building that would house the engineering department and the corporate offices.

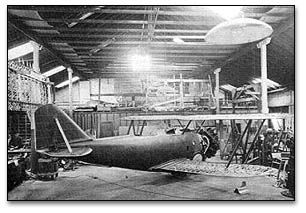

The XFF-1 is gradually taking shape as seen here in late October, 1931. Shortly after this photo was taken, the XFF-1 was moved by truck to Grumman's new facility at Curtiss Field in Valley Stream Long Island. (Mfg. photo)

Grumman’s move to the new accommodations was made on November 4, 1931. It took three days to truck everything over and set up shop. When the incomplete XFF-1 arrived at the hanger, work resumed at the former hectic pace. A few weeks later, the expected contract for the Model B floats arrived, an early Christmas gift from the Navy. Things were rapidly winding up to a climax. With each passing day, the XFF-1 was closer to being ready for its first flight. Tension and excitement mingled as the last work was completed on the new fighter. It was time to see if the efforts of the past nine months would be rewarded.

In the freezing cold morning air of December 29, 1931, the XFF-1 was rolled out of the hanger into the morning sun. Carefully, the fighter was subjected to an intensive pre-flight inspection. Once everything had been checked, re-checked and then triple-checked, it was deemed ready to fly. Test pilot Bill McAvoy climbed aboard. With the engine started, McAvoy went through his checklist and taxied to the end of the grass field. After a magneto check, McAvoy eased the throttle forward and the new plane surged down the field and eased off the ground. Cranking the landing gear wheel, McAvoy pulled up the wheels. This first flight was supposed to last more than two hours, but within thirty minutes, the XFF-1 was back. Since there was no radio, no one understood why the flight had been aborted. McAvoy landed and taxied over the hanger. At first glance it was obvious that something was very wrong. Streaked in oil, the fighter braked to a stop in front of the open hanger door. As soon as the engine was shut down, Grumman mechanics swarmed all over the little biplane. In a matter of two minutes, the problem had been discovered. The filler cap on the oil tank had not been properly secured. Under pressure, oil was blown out and it covered the fuselage and the cockpit glass. After cleaning the oil from the plane and topping off the oil tank, the cap was fastened securely and McAvoy took off again to finish the test flight.

After being successfully tested by Grumman, the XFF-1 was turned over to the Navy for acceptance testing. Here the stubby Grumman can be seen during the Navy tests at NAS Anacostia in late 1931. (U.S. Navy photo)

At the conclusion of Grumman’s test flights, the Navy took custody of the XFF-1 and began their own series of tests. Aside from some minor bugs, the XFF-1 was everything Grumman had claimed it would be. Handling and maneuverability were excellent. Climb and ceiling were adequate if not exceptional. Most impressive was the plane’s speed. It proved to be considerably faster than the Navy’s current single-seat Boeing F4B-4 fighter. During speed trials, the XFF-1 attained a maximum speed of 195 mph.* Overall, the XFF-1 outperformed anything in the Navy inventory. Better yet, no major changes would be required. Grumman had designed it right on the first try.

* Earlier, in August of that year, Granville Brothers Aircraft would design and fly their outrageous monoplane racer, the Gee Bee (for Granville Brothers) Super Sportster Model Z. Designed to compete in the National Air Races, the littl e black and yellow speed demon won every event it started, including the prestigious Thompson Trophy race. Remarkably, the tiny and over-powered plane would eventually attain a speed of 314.47 mph in November of 1931. Beginning in 1929, civilian racing planes would badly out-speed the land planes of the world’s military forces. This trend would continue until the middle 1930s. At the beginning of World War Two, many of the fighters in service with world’s Air Forces could not achieve the speed of the 1931 Gee Bee. Yet, the Model Z was a true contemporary of the FF-1. Ironically, the designer of the Model Z, Robert Hall, would later be hired by Grumman and fly as the company’s chief test pilot and eventually, Vice President of Engineering. Hall retired in 1970.

At a time when 200 mph was considered to be a tremendous speed for military fighter aircraft, the Granville Brother's Gee Bee Model Z was exceeding 314 mph. This photo of the Model Z was taken on its maiden flight in August of 1931. At the controls is the little racer's designer, Bob Hall. In early December of 1931, the Model Z and pilot Lowell Bayles were tragically lost while attempting to set a new world speed record at Wayne County Airport in Mich igan.

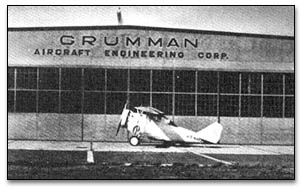

While the Navy continued testing of the XFF-1, Grumman was busy constructing the XSF-1, which would fly in August, 1931. Shortly thereafter, the Navy awarded Grumman with a contract to build the XJF-1 Amphibian prototype. By the end of the year, the Navy accepted the XFF-1 and issued a contract for 27 FF-1 fighters. With contracts in hand totaling nearly $750,000, Grumman was in the aircraft business for the foreseeable future. Ultimately, 34 SF-1 Scout fighters would also be ordered. Soon, work would begin on the XJF-1 and once again, Grumman would out-grow its facility. Relocating to Farmingdale, Grumman would occupy a bigger building and share the local airfield with another struggling aircraft manufacturer, Seversky. With the coming of 1933, Grumman was about to explode in growth.

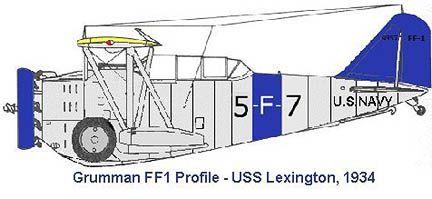

Shown in the colors of VF-5B assigned to the USS Lexington, the FF-1 shows off its bulbous forward fuselage. This was made necessary by the design of the retracting landing gear. (C.C. Jordan Image)

With the FF-1 nearing the beginning of its production run, Grumman’s management turned their attention to something close to Leroy’s heart. For years the Navy was operating Loening OL amphibians. However, being first flown in 1923, these were badly in need of replacement. Grumman retained the basic layout of the Loening, but the new design was far more refined. By deepening the centerline float, Grumman was able to lower the thrust-line of the engine, which greatly improved forward vision. Designed with an all-metal semi-stressed monocoque fuselage, the new airframe was quite advanced for the time. Wing construction was also of aluminum alloy, with fabric covering. When the design team was satisfied with their proposal, it was forwarded to the Navy, who immediately issued a contract for one prototype.

Now quite old and lacking in performance, the Loening OL series had been in service since the mid 1920s and was well past its prime. This OL-8 was still providing day to day service when Grumman proposed its replacement in 1932. One can see that the thrust line of the engine is very high in relation to the cockpit. This was caused by the switch from a narrow liquid cooled engine to a large diameter radial in later variants. Vision over the radial engine was non-existent.

April 24, 1933 presented Grumman’s personnel with the promise of an unusually warm spring day. The XJF-1 was carefully pushed out onto the apron and preparations were then made for the amphibian’s first flight. Fuel and oil were checked and rechecked. As a small crowd of Grumman employees stood by, the engine was started and the ungainly aircraft taxied out. Positioned at the end of the field, the test pilot performed his pre-take-off checks. Everyone heard the engine increase in speed and noise, then die down after a magneto check. Seconds later, they heard the power come up again as the pilot advanced the throttle until the engine’s manifold pressure stabilized at 30 in/hg. Brakes were released and the big biplane began to roll. Slowly feeding in power, the pilot guided the XJF-1 down the field. Acceleration was much better than anyone would have imagined. Without the slightest backpressure on the control stick, the plane flew itself off the field. A pronounced wobble was seen by those watching from the ground as the pilot cranked the gear retraction handle around for 47 exhausting turns to pull up the landing gear. Entering a gentle bank, the XJF-1 turned north and disappeared from sight.

It would take only one flight to establish that the XJF-1 was a vast improvement on the Loening OLs currently in use by the Navy. The original prototype was armed, with a .30 caliber Browning machine gun clearly visible in the rear cockpit. Only the vertical stabilizer would change substantially before the new amphibian entered production as the JF-1 in late 1934.

This first flight and subsequent test hops would reveal a necessity to reshape the vertical stabilizer. Some other minor details would requ ire attention, but once again, the basic design proved to be sound. After the Grumman was satisfied with their efforts, the amphibian was turned over to the Navy.

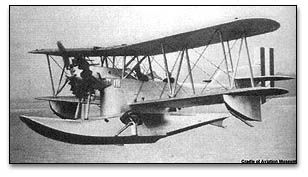

This excellent landing photo of a Coast Guard JF-2 reveals the narrow track of the landing gear. Untypical of most biplane amphibians, the Grumman JF series offered excellent performance and superb utility.

Navy testing revealed a baseline improvement over the Loening that was nothing less than startling. Maximum and cruise speeds were very impressive, being more than 40% faster than the older aircraft. Climb rate was more than 50% greater than the latest OL-9. With a service ceiling of 25,000 feet, the Grumman could climb nearly 11,000 feet higher than the tired, old Loenings. Being fully equipped for carrier operations, the XJF-1 was exactly what the Navy wanted and needed. With few changes, a contract was issued for twenty-seven JF-1s with the first to be delivered in late 1934.

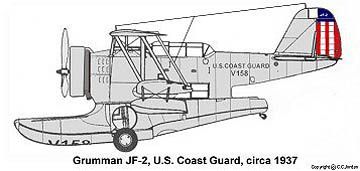

Named the “Duck”, the JF-1 would evolve through six major variants. Seeing that the JF-1 would be perfect for their needs, the U.S. Coast Guard ordered 14 of the amphibians, without arresting gear and ordered that the Pratt & Whitney R-1830 engine of the JF-1 be replaced with a larger diameter Wright R-1820. Designated the JF-2, these Ducks would go on to give sterling service for many years.

This revealing photo was taken by renowned aviation photographer, Gordon Williams. Viewed from the cabin of a Douglas RD-4, this JF-2 shows it serial number painted on the underside of the float. The snowcapped mountains in the distance indicates that this JF-2 was stationed in the northwest, likely in Washington state.

Typical of the Coast Guard JF-2, the tail hook of the JF-1 had not been installed. While the JF-1 was powered by a twin row Pratt & Whitney R-1830 radial, the Coast Guard opted for the larger diameter Wright R-1820. This did reduce visibility over the nose somewhat, but was still far better than the old Loenings.

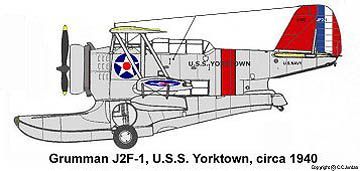

Later, the Navy would also adopt the R-1820 engine, and these powered the JF-3. In 1937, the designation was changed again with the improved J2F-1. This was the first variant with noticeable modifications to the airframe. The rear of the float was extended and the area above this was substantially filled in with new structure.

Along with a change of designation, the J2F-1 introduced several significant airframe changes. Earlier models used an external strut to link the upper and lower ailerons. This was replaced by an internal linkage. To obtain better in-water handling, the float was lengthened and the structure above this was largely filled in. This also had the advantage of improving ground handling by moving the tail wheel further aft and reduced any tendency to weather-cock in a strong wind.

Earlier Ducks had a strut connecting the upper and lower ailerons. This was done away with on the J2F-1 and the linkage was moved to the inside of the wing. With the coming of the war, Grumman needed every bit of production capacity for fighter production. As a result, the last 330 Ducks ordered were to be built under license by Long Island’s Columbia Aircraft Corporation. Despite not being built by Grumman, the Navy gave them the Grumman designation of J2F-6.

Even as Grumman tooled up to begin production of the FF-1, another new fighter design was underway. It seemed only logical that the performance advantage of the FF-1 would be very short lived. To maintain their position, Grumman certainly understood that continuous research and development was an absolute necessity to remain competitive.

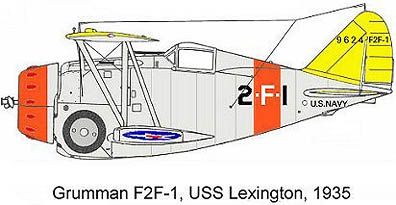

Grumman's tubby little F2F-1 was well received within the fleet. This fighter was assigned to VF-2B, which was deployed aboard the U.S.S. Lexington. They replaced the aging Boeing F4B-1 then in service with the squadron.

It would be difficult to improve performance with another two-seat fighter and Grumman prepared a proposal for a new carrier borne single seat fighter. Being very much pleased with the FF-1, the Navy did not hesitate to give Grumman a contract for a prototype designated the XF2F-1. The general arrangement would be similar to the two-seater FF-1. However, the overall dimensions would be considerably reduced. Carrying over the same landing design only magnified the squat, tubby appearance o f the new biplane. While production of the FF-1 proceeded, the XF2F-1 was completed and prepared for its first test flight. Rolled out into the Long Island sunshine, the little biplane gleamed in its new paint. Its all-metal fuselage was state of the art. Powered by twin row Pratt & Whitney R-1535-44 radial generating 625 horsepower, the prototype simply leapt into the air after a short take-off roll. The XF2F-1 demonstrated a top speed of 229 mph., and climbed at the phenomenal rate of 3,130 feet per minute. Maneuverability was equally outstanding. After initial testing was completed by Grumman test pilots, the prototype was delivered to the Navy at Anacostia Naval Air Station. Not unexpectedly, the Navy was pleased to find that the aircraft was even better than they had anticipated. Just five months after its first flight, a procurement order was issued to Grumman on March 17, 1934. Within a year, the first production F2F-1 fighter was delivered and accepted.

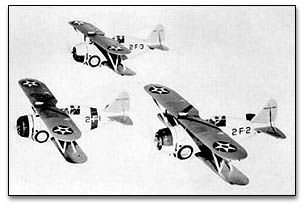

Three of VF-2B's F2F-1 fighters fly the typical V formation. It is interesting to note that the various planes of each flight could be discerned not only by the fuselage numbers, but by the painted portion of the engine cowling.

When the F2F-1 entered into service, it appeared with a refined cowling and a more powerful R-1535-72 engine. Top speed had increased slightly to 231 mph, and the rate of climb had dropped slightly due to the weight of added equipment. Still, performance was considered excellent and the fighter proved to be extremely popular with its pilots. The first squadron to receive the new fighter was VF-2B aboard the U.S.S. Lexington. Other squadrons to fly the F2F-1 were VF-3B on the U.S.S. Ranger and VF-5 deployed on the U.S.S. Wasp. These fighters would remain in front line service until they were eventually replaced by the F3F and later, by new monoplane fighters in 1939 and 1940. Though relegated to training duties, the F2F would soldier on throughout the war giving good service to a new generation of Naval Aviators.

Shown in the colors of VF-2B assigned to the USS Lexington, the F2F-1 shows off its remarkably squat fuselage. Called the "Flying Barrel", the F2F-1 was an excellent performer despite its less than sleek profile.

Shortly after the first F2F-1 was delivered, the next Grumman fighter made its first flight. Designated as the XF3F-1, it had been ordered the previous October. Essentially, the F3F was a redesign of its earlier F2F sibling, incorporating a slightly more powerful version of the Pratt & Whitney R-1535 than that fitted to the F2F. This new design produced less aerodynamic drag, and even though it was nearly 600 lbs heavier, it was more than 20 mph faster, although this extra weight resulted in a reduced rate of climb. Perhaps of greater importance to those who tested and flew the fighters, was the significant increase in overall maneuverability that accompanied the redesign.

After the loss of the first two XF3F-1 prototypes, the third finally made into acceptance trials. This photo was taken on January 10, 1936, just 20 days before the first production F3F-1 was delivered to the Navy.

The development program would suffer from the loss of two prototypes. One of which was caused by structural failure. In August of 1935, the Navy issued a contract for 54 F3F-1 fighters, the first of which was delivered on January 29, 1936. Despite the two crashes, the Navy was still very impressed with the new Grumman and their faith was fully justified once testing had begun on the third prototype.

With the F3F-1 now in service, and being well liked by its pilots, Grumman proposed that the last aircraft of the order be delivered with a more powerful Wright R-1820-22 Cyclone producing 850 hp. Approval was granted by the end of July, and thus was born the XF3F-2. Fitted with the nine cylinder Wright radial with its much greater diameter, the XF2F-2 appeared even more portly than its predecessors. Nonetheless, looks have always been deceiving when it came to Grumman aircraft, and this one was no different.

Flight testing revealed that overall performance had improved, despite the significant increase in diameter of the engine and its inherent drag. Helping to convert the increased horsepower into thrust was a new three-blade, adjustable propeller. The Navy promptly placed an order for 81 of Wright powered fighters. And why not? Grumman's little F3F had evolved into one of the world's best biplane fighter aircraft.

His canopy pushed full open, this VF-4 pilot enjoys the view over California. His F3F-1 carries a unit designator that indicates that this pilot is the leader of the VF-4s second section.

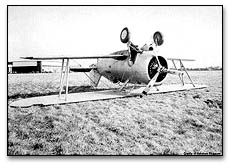

Landing on rough ground always presented the risk of digging in a wheel or catching a prop tip. Exactly how the XF3F-2 prototype came to find itself in this position can't be determined by this photo. It did, however, bend only the top propeller blade, which leads me to believe that the engine was not running when the fighter nosed over.

Not all F3F fighters went to the Navy. The Marine Corps fielded VMF-1 and VMF-2, both equipped with the F3F-2. Marine fighter pilots found the tubby F3F much to their liking.

On December 1, 1937, the Navy accepted the first F3F-2, with the last being delivered on 11 May 1938. It was determined that another squadron of F3Fs were needed and the Navy placed an order for 27 improved F3F-2 fighters, plus one prototype which was given the designation of XF3F-3.

These aircraft incorporated subtle improvements to the aerodynamics (largely to to engine cowling, which was a major source of drag) and equipment. These ‘cleaned up’ aircraft managed to attain a maximum speed of 264 mph, or 33 mph faster than the F2F-1 of two years earlier

A Navy test pilot, with controls crossed, presents a planform view of the XF3F-3 undergoing testing at Anacostia Naval Air Station.

Ultimately, the F3F would remain in service aboard U.S. Navy fleet carriers until the spring of 1941. Being retired from front-line service did not consign the F3Fs to the scrap heap. They would go on to serve in the Naval Reserve and were extensively used as advanced trainers during the first year of America’s involvement in the Second World War.

Color profile of the previous VF-5 aircraft.

With the day of the carrier borne biplane clearly at an end, the Navy issued a requirement for a monoplane fighter and announced a competitive fly-off. Grumman was requested to submit a biplane design, as the Navy wanted to hedge its bets against the possibility that the monoplanes would not prove to be acceptable. Grumman proposed a yet another improvement on the F3F.

Flying over the coast of southern California, a trio of USS Yorktown F3F-3 fighters form up in the standard V-formation employed at the time. Leading the formation is the same 5-F-1 Grumman from VF-5.

It would be longer, and have a greater wing span, with the upper and lower wings being of the same span for the first time. Designated as the XF4F-1, Grumman realized that the fighter would be at a distinct performance disadvantage to the competition, which included the Brewster XF2A-1 and the Seversky XFN1-1. Therefore, Grumman presented a strong argument that they be permitted to submit a monoplane design as well. The Navy agreed and thus was born the XF4F-2.